Mutual Interest Develops in Heritage Restoration

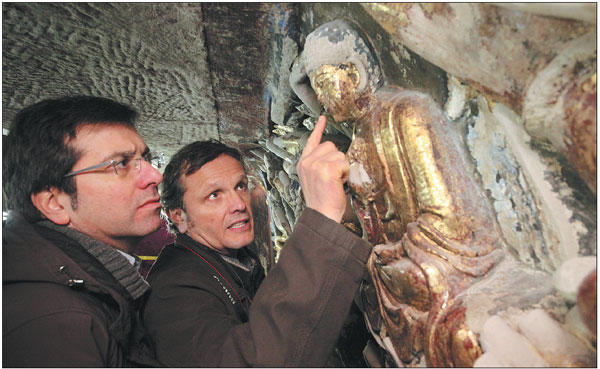

Italian experts help to restore statues of Bodhisattva of Mercy at a temple in Chongqing. [Photo by Luo Jiaguo/For China Daily]

Italian academics share their knowledge to help preserve unearthed ancient relics.

Italy is a leader in the restoration and conservation of art and archaeology. Its experts are frequently called upon by countries around the world. This includes China, which is second only to the Mediterranean peninsula in terms of UNESCO World Heritage sites. Italy has 54 and China has 53.

Xinhua interviewed some of these experts to find out how exchanges between the two countries run.

Among them is Gilberto Corbellini, a professor who directs the Department of Human and Social Sciences and Cultural Heritage at the National Research Council - also known as the CNR - in Italy, an institution whose long-standing relationship with China dates back more than 20 years.

In 2014, the CNR entered into an accord with the Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage. Both institutions select three-year projects they want to work on together, with each side putting in a share of the financing.

"Cultural heritage should be seen as the result of innumerable human choices, stratified over centuries and millennia," Corbellini wrote in a foreword to the 2018 book China and Italy: Routes of Culture, Valorization and Management. It was edited by CNR researchers Heleni Porfyriou and Bing Yu.

"This makes cultural heritage a vital part of a community, as the result of the sensitivity, thoughts, expectations, problems of men and women who, with their identities and personalities, have built the reality in which we live today," Corbellini wrote.

"I had the opportunity to meet and talk with the CACH director, and what emerged clearly is that there is a mutual interest, especially in the field of training," Corbellini told Xinhua. "On the one side, the possibility of transferring knowhow and technology to restorers and cultural heritage scholars in China. While at the same time, the opportunity to develop specific interventions together, in China, that are tailored to local cultural needs and expectations."

But what makes Italy a leader in this sector and why do Chinese archaeologists and scholars seek out its experts?

According to Porfyriou, it is because Italy has an extraordinary tradition in terms of a theoretical approach.

"It was the first country to engage in an interdisciplinary line of reasoning in this field. It was also in the vanguard on urban conservation, which Italy tabled at the beginning of the 20th century, while the rest of Europe only began to address it in the 1960s," she said.

Also, Italy has "a wealth of art and monuments, which allowed it to apply and demonstrate its theories to the world," said Porfyriou. For the past eight years, she has been working on a comparative project with China on its so-called "water cities", which are comparable to Italy's historic medieval villages, or borghi.

"Some are near Shanghai, so they benefit from tourism. But others have been abandoned, exactly like some of Italy's borghi," she said. "Our project is bilateral and seeks to identify practices allowing both countries to create parallel, similar networks that not only learn from each other but also benefit from an increased awareness that is also inclusive of the local population.

"We found that the local populations are interested: there is the same sensitivity toward history and tradition that exists among the public in Italy," Porfyriou said.

Archaeologist Maria Concetta Laurenti, a professor at the Superior Institute for Conservation and Restoration in Rome, said it is Italy's scholarly and scientific roots that make it a leader in this field.

"We developed this debate earlier than other countries did," Laurenti told Xinhua. "We started thinking about this issue in the 1800s and this ultimately culminated in the setting up of our institute in 1939.

"A need had been felt of giving a scientific foundation to the restoration of works of art. Until then, restoration had been confined to artisans' workshops, where certain methods were jealously guarded secret recipes," Laurenti explained.

Bringing restoration out of the workshop, giving it a scientific basis and founding a school to train restorers to be technicians, not artists, contributed to Italy's leadership in this field, she said.

What distinguishes Italian experts from their Western peers is a sensitivity that goes beyond a scientific assessment of the job. They identify the causes of decay and intervene to limit the damage and restore the piece to a certain condition, Laurenti said.

"We don't recreate, we don't remake, we don't falsify," she said. "A lot also depends on (the individual restorer's) capacity, sensitivity to color, and the sensitivity with which the work is treated. We have developed this sensitivity to a great degree, also thanks to the schools for restoration we have here in Italy."

These schools include the Department of Restoration and Conservation at Tuscia University. One of its founders is Salvatore Lorusso, a professor who also founded and directed the Laboratory for Cultural Heritage at Bologna University.

Lorusso, a professor emeritus and former visiting professor at Zhejiang University's Cultural Heritage Institute in China, was contacted by Chinese archaeologists when the Qingzhou Buddhist sculptures were discovered at the Longxing Temple in 1996.

The statues, he said, dated back to a period between AD 500-1100. "The cleaning presented huge problems, because previous restorations had been done using incorrect products and substances," Lorusso told Xinhua.

"So we moved onto innovative methods using biological substances to remove the dirt and the patina that encrusted the surface of those fantastic statues."

Describing himself as "fundamentally a diagnostician and a chemist," Lorusso went on to explain that restoration and conservation is an interdisciplinary field.

"Why interdisciplinary? Because I always need others and equally, others need me," said Lorusso, who founded the journal Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage. He has also authored more than 420 national and international publications.

"The human sciences must proceed hand in hand with the experimental sciences. The scientist must work with the art historian and the archaeologist."

CNR researcher Porfyriou said that "our Chinese colleagues (in restoration and conservation) have a great desire to spread and raise awareness, both among local decision-makers and among the public."

A key part of this awareness is a project that twins historic sites of the two countries through UNESCO. This would show that "funding and well-being and urban quality do not come only from tourism, but also from the championing of historic urban settings and buildings," Porfyriou said.