Metal, Lacquer and Clay

Wu Zhongfeng is making Mongolia marquetry works. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Three masters share their thoughts on the development and promotion of traditional handicraft, Wang Ru reports.

Wu Zhongfeng was impressed by mengxiang, or Mongolian-style craft of inlay, which "can turn metal into doughlike soft things" at the age of 16, when she started to learn the craft of making such work in metal and other materials from craftsman Kang Wensheng in Beijing in the 1970s.

Wu's devotion to the craft for the past 40 years has turned her into an official inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage called "Beijing Mengxiang". Along with two other masters, who specialize in lacquerware carving and clay figurines, Wu participated in an activity held by a Beijing-based association to promote the development of cultural heritage in the city on March 20.

The Mongolian-style craft of inlay comes from the nomadic tribes of the Mongolian and Tibetan groups, who inlay precious stones for decorative objects by chiseling, carving, welding, gilding and polishing. The craft uses metal. Wu calls it a fire art, and stresses the importance of temperature in this craft.

In 1862, some artisans who were good at chiseling copper, established the Ronghe Copper Shop with the help of Zaobanchu (Bureau of Imperial Production) located in the Forbidden City to make figures of the Buddha, ritual instruments, gold and silver wares used in the then royal court. The handicraft used was called mengxiang.

Since this craft had royal patronage, the works are often exquisite.

"That is the taste of mengxiang. We try to create works that have shine - gold or silver in them - but also a sense of history," says Wu.

She usually uses the craft to replicate cultural relics while also trying to discover their deeper meaning when traveling.

She once found a cultural relic at the Sakya Monastery in the Tibet autonomous region, and she tried to replicate it and created a Mongolian-style inlay work.

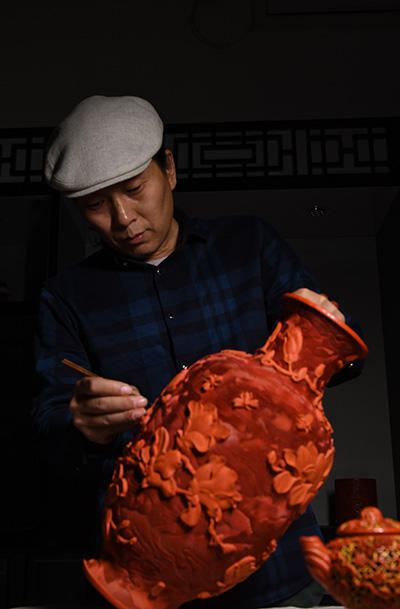

Li Zhigang is making lacquerware carvings. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Royal patrons

One of the "eight marvelous handicrafts of Beijing", lacquerware carving was also passed down from the royal court in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Li Zhigang, an expert of the carving, started to learn this craft in his teens. He introduced its history, dating to the Tang Dynasty (618-907), to the audience in Beijing this month.

The craft prospered in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), with Zhang Cheng and Yang Mao as two main masters at the time. It continued to develop both in the Ming and Qing dynasties but declined at the end of the Qing rule. After New China was founded in 1949, the craft began to develop again.

Lacquerware carving needs to go through at least 10 production processes, according to Li. Simply the procedure of spraying paint on the body of the work takes over half a year. Craftspeople usually have to spray repeatedly for about 120 times in a room with the temperature at 27 C and humidity at 80 percent, making people feel like they are in a sauna.

Though this craft has a long history, it has combined many modern elements today.

A typical example is Qimu, an iconic work by Li that looks like a pregnant woman standing and staring into the distance.

Yao Xiaojing is making a clay figurine. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Common inspiration

The other master craftswoman, Yao Xiaojing, introduced Clay Figurine Zhang at the Beijing event. It was created by Zhang Mingshan who lived in what is now Tianjin in the Qing era. The quick-witted and nimble-fingered man observed people from all walks of life in the streets, and made vivid and lifelike clay figurines.

In 1905, a third-generation member of Zhang's family was invited by late premier Zhou Enlai to promote the craft in Beijing, and a branch in the city was established.

Yao is a student of a fourth-generation inheritor in making the Zhang style of clay figurines and an expert in the Beijing school of this craft.

"Some people say the only difference between works of Zhang and real people is that the clay figurines cannot breathe, showing how vivid the works are," says Yao.

At the Beijing event, the master craftspeople discussed the development of cultural heritage and encouraged integrating modern elements into traditional art.

"We must keep pace with the times, so that the crafts survive in the modern world," says Yao.

"People in our industry have an average age of above 50, we lack younger participation," says Li.

Wu says she wants to cultivate talented people to take her craft forward, saying three young people work with her.

"But thanks to China's emphasis on such handicraft since 2006, some specialized schools now enroll students to learn them, so as to cultivate young inheritors," says Li, who is an adviser to graduate students on lacquerware carving at an art and craft school in Beijing.

Ordinary people also have more access to such handicraft today. The experts have opened studios that enable people to learn these crafts.

"Although many people just learn the crafts for fun, they are really excited during the process," says Yao.