Decoding history's bones

Exhibition details China's earliest-known writing system in display of precious archaeological artifacts, Wang Ru and Shi Baoyin report.

During an international academic seminar in 1989 commemorating the 90th anniversary of the discovery of jiaguwen (oracle bone inscriptions) from the Yinxu Ruins in Anyang, Henan province, a foreign scholar said it was a pity he couldn't view the bones in their original setting but hoped that one day, the bones scattered around the world would return.

The words struck a chord with Song Zhenhao, an expert on jiaguwen and academician committee member from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, when he attended the seminar. The dream finally came true recently as some of the earliest discovered oracle bones, which are now stored in Tianjin Museum, traveled to the Yinxu Museum in Anyang for a new exhibition.

The Show of King's Return: The Inscribed Oracle Bone Collections of Tianjin Museum Back to the Great Settlement Shang displays precious artifacts discovered in the Yinxu Ruins in the late 19th century. This is the first time this batch of oracle bones is returned to where they were unearthed.

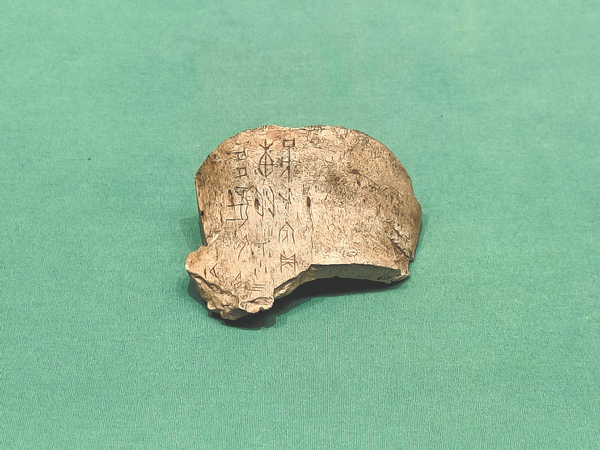

The bones were used for fortunetelling, as well as recording and composing the earliest-known formal writing system in China. In 2017, the inscriptions were listed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register program.

According to the exhibition's curator Zhang Xia, Tianjin Museum houses more than 1,700 oracle bones spanning the late Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC) from collectors who played significant roles in obtaining them during the turbulent 20th century.

The 36 bones on display are carefully chosen from the large collection, all directly related to King Wu Ding of the Shang Dynasty, describing his sacrifice, war, farming and husbandry, officials and consorts.

Shang Dynasty stories

Wu Ding diligently worked to strengthen the dynasty, reform governance and appoint capable officials, earning him the title "reviver of the Shang Dynasty". His many deeds were recorded on oracle bones and passed on to modern society, says Zhang.

"We want to show the best stories of Wu Ding from the oracle bones he left behind," says Zhang.

Wang Wei, a veteran archaeologist from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says Wu Ding's reign was one of the most prosperous of the Shang Dynasty, with detailed records carved into oracle bones that offer a glimpse of the era's social structure.

A complete oracle bone on display shows the four-part fortunetelling process — first, learning about the person and time to practice divination; second, the detailed things Wu Ding wanted to ask the god; the third part records his judgment of good or ill luck according to information on the bones, which usually comes from the cracks formed after being fired; and finally, the verification of the results, says Zhang.

"This bone describes a day when Wu Ding ordered someone named Que to predict his fortune to see if something disastrous would happen in 10 days. He judged from the cracks that it would happen. Three days later, a northern wind came during a sacrificial ritual, so they believed the prediction was accurate," he adds.

"Only rare bones have the complete four parts. Many are broken or have some unclear words due to the passage of time."

A small bone on display records a divination paying tribute to an earlier Shang king with elephants as sacrifice. "The word 'elephant' in jiaguwen seems to imitate the elephant's shape. This bone tells us that Yinxu was very moist, and elephants roamed during the late Shang period. Archaeological studies prove that by the elephant bones unearthed there. It sheds light on Anyang's ecological environment 3,000 years ago," says Zhang.

Another bone on display shows ancient people's understanding of rainbows. "The word 'rainbow' is similar to its shape in jiaguwen. Ancient people saw a curved band of different colors straddling a river and thought it was a mythical beast drinking water. They worried if the beast would drink all the water without leaving some for the people. So, they practiced divination to know if they wouldn't have water to drink and if their crops would harvest in the future," says Zhang.

According to He Yuling, head of the Anyang workstation affiliated with the Institute of Archaeology with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, understanding the Shang civilization is a major aspect of why scholars study the bones, and another is to identify the words on the bones.

As of now, Yinxu has yielded more than 150,000 inscribed oracle bones, on which there are more than 4,500 words. One-third of them have been decoded, says He.

Wandering relics

Discovered in 1899, inscribed oracle bones were first bought by antique dealers from Anyang and sold to Tianjin and Beijing. There, they were accidentally discovered and collected by late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) official Wang Yirong, epigraphy specialist Wang Xiang and some others. Many of their collections were later donated to Tianjin Museum. Some of the bones were also transported overseas and are now stored in more than 200 institutes across the world, according to Song, the jiaguwen specialist.

"In their long tale, they have met numerous people and passed through many hands and places," he says.

Although later oracle bones were unearthed in archaeological efforts in the Yinxu Ruins, the early batches never returned until this exhibition, which will run until May.

"When the bones were discovered, China was undergoing a tumultuous phase, facing a barrage of influences from foreign cultures. At that time, Chinese people were disheartened and grappling with doubts about their own cultural heritage. But the oracle bones were a gift from ancestors, which enabled them to realize again the country's profound culture and gain courage and confidence to pass it on," says Song.

"The magical bones live in my heart and I think they are eager to return to their origin. Wishes are difficult to realize … I wonder how they will return, even for a while."

According to curator Zhang, in archaeological studies, the emphasis is often placed on preserving cultural relics at their original sites. "Context is crucial; displaying the same artifacts in different locations can significantly alter their meaning. Anyang is the home of the bones. Therefore, their return is many senior jiaguwen specialists' decades-long dream," says Zhang.

Song says the oracle bones from Tianjin Museum stand out not only because they belong to the early unearthed batch, but because they are large with many words and diversified content related to the geographical conditions, climate, farming and hunting, transportation, military affairs, religion and daily details of people during the last Shang period.

He is especially impressed by a piece stored at the museum that has words in different sizes. Some words are about 3 centimeters in length and width while others are 0.5 cm — all from the same article.

It's like a calligraphy work in which the writer changes the style with his emotions. The words are not in a standard printed style. The contrast in their sizes makes you feel someone was carving them by hand instead of using a machine, he says.

"I stared at the inscriptions and was immersed in communicating with ancient people. I felt its traces of life," says Song.